BOOKS

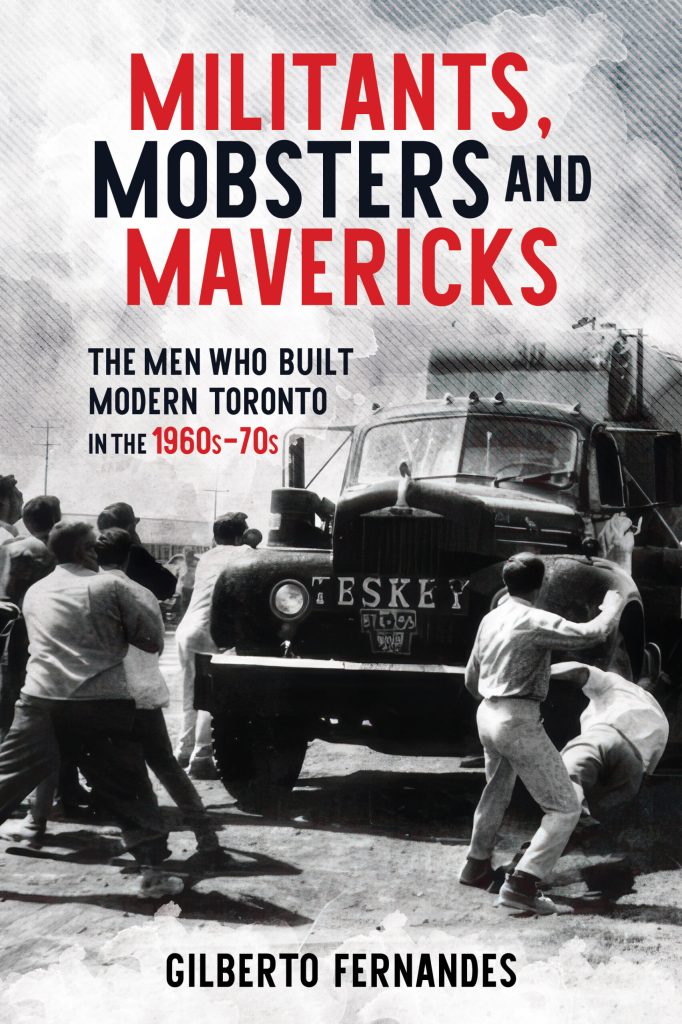

Militants, Mobsters and Mavericks: The Men Who Built Modern Toronto in the 1960s–70s (Toronto: Lorimer, Fall 2026)

Here is a gripping look at the underbelly of Toronto’s explosive postwar growth, when labour leaders, politicians, contractors and crime figures battled for control of the city’s booming construction industry. Toronto’s highways, subways, and skyscrapers were built by immigrant workers under dangerous conditions, while they fought for fair wages and better safety measures. Militants, Mobsters and Mavericks tells the story of fiery union leader Gerry Gallgher and his cerebral successor Giovanni Stefanini, whose battle for workers made them allies, or foes, of a remarkable cast of Toronto figures of the era, including journalist-turned-politician Frank Drea, idealistic coroner Morton Shulman, and Hamilton Mafia boss Johnny Papalia. The fast-paced narrative explores a little-known side of Toronto’s history, and how building trade unions, like the powerful LIUNA, with its 70,000 Toronto-area members, gradually moved away from supporting the NDP towards the provincial Conservative party.

Expected publication, October 7, 2025.

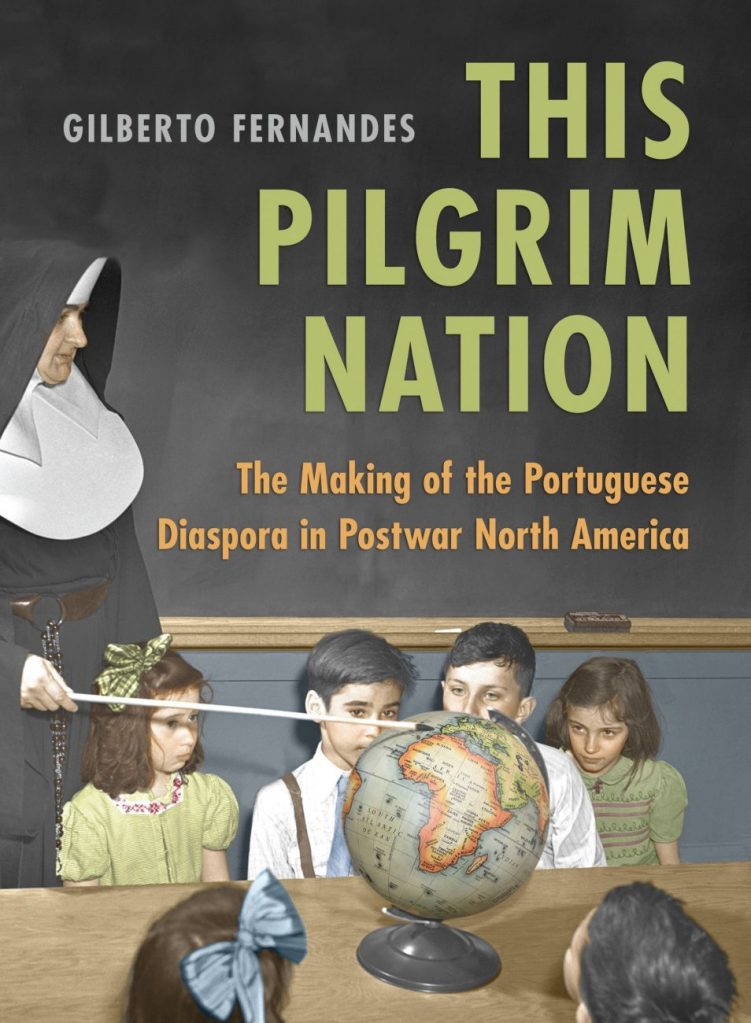

This Pilgrim Nation: the Making of the Portuguese Diaspora in Postwar North America (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019)

This book tells the transnational history of Portuguese communities in Canada and the United States against the backdrop of the Cold War, the American Civil Rights movement, the Portuguese Colonial Wars, and Canadian multiculturalism. It considers the ethnic, racial, class, gender, linguistic, regional, and generational permutations of “Portuguese” diaspora from both a transnational and comparative perspective. Besides showing that diasporas and nations can be co-dependent, This Pilgrim Nation counters the common notion that hybrid diasporic identities are largely benign and empowering by revealing how they can perpetuate asymmetrical power relations.

CHAPTERS AND ARTICLES

w/ Roberto Perin, “Homebound Revolutions: Portuguese Immigrant Activists in Montréal During the Long Sixties,” in Abril Liberatori and R. Perin eds., Making Immigrants Insiders: New Directions in Canadian Migration History (UBC Press, forthcoming)

What is a decade in history? A mere ten years? In the personal histories of the Vianas, a family of leftist anti-fascist activists who lived in Montreal between 1965 and 1975, those ten years were a cornerstone in the edifice of their lives. It had the same importance as what national histories attribute to decades like “the Sixties.” For Canada and Québec, this important decade is full of social, cultural, and political meanings informed by the many progressive movements that emerged and intersected during that period. In contrast, in Portugal “the Sixties” did not happen, only the 1960s. This chapter reflects on the Vianas’ experiences and realizations as politically active, cultured, educated, middle-class immigrants in Montreal during the Quiet Revolution; their involvement with the anti-fascist Movimento Democrático Português and other progressive exiled organizations; their simultaneous sense of liberation and disillusionment following the Carnation Revolution of April 25th, 1974 and the family’s return to Portugal, where feminism and other causes of the “Sixties” New Left were incipient in the party-led and traditionally Marxist revolutionary process.

This article examines how construction machines shaped the gender, class, and racial constructs of operating engineers by simultaneously augmenting, weakening, and subsuming their bodies. It discusses the changing representations of their symbiotic relationship in union journals, newspapers, children and youth books, poetry, magazines, advertisement, and other popular media, and what they reveal about shifting North American views on technology and masculinity. Originally described as feminine dragon-like mashenes tamed by masterful men, subsequent generations would depict the operators’ relationship with their human-like technology as intimate partnerships, and later as that of paternal figures and their boyish machenes. An undercurrent view represented construction machines as sentient servants with the power to replace working men’s brawn and eventually their operating masters’ brains. The article identifies overlapping and competing trends that became dominant in different periods, and shows how interconnected ideas of technology and masculinity adapted to changing contexts to maintain white male dominance of this skilled trade.

There have never been more favourable conditions for drawing Indigenous workers into the unionized building trades. The construction industry needs to replenish and diversify its overwhelmingly white male and aging workforce to meet its skilled labour demands for the next few decades, when major civil infrastructure, mining, and green energy developments are expected to happen in northern Indigenous territories. These projects will be mandated by Impact Benefits Agreements to employ a significant number of Indigenous workers who will first need to be trained. At the same time, Indigenous peoples are the fastest-growing population in Canada and have shown a propensity for pursuing trades education. In recent years, Ontario’s largest building trade unions have taken significant steps to recruit, train, and employ northern Indigenous workers, including in Nunavut. In collaboration with various stakeholders, their efforts are starting to show positive results. But are their methods and goals informed by decolonization, reconciliation, and indigenization? This article reflects on this question while examining the case of the International Union of Operating Engineers, Local 793, which has been a leader among building trades unions when it comes to establishing relationships with Indigenous partners, training Indigenous workers, and contributing to their economic self-determination.

Since the late nineteenth century, Canada required modern construction machines for industrial growth. Thanks to their novelty and visibility, these machines entered the Canadian psyche, symbolizing hopes and fears about the relentless transformations of modernity. Metaphors depicting these machines as zoomorphic and monstruous reflected the environmental-technological infrastructures they built, which redefined nature through technologies like trains, ships, and automobiles. This article discusses how Anglo-Canadians, particularly Ontarians, interpreted technology, drawing parallels with the automobile’s history. Both had a problematic coexistence with humans as equally empowering and oppressive mobile machines that were imposed on public spaces and constructed as necessary for progress. The builders used the machines’ allure to present construction as an inclusive civic spectacle and foster public tolerance for their relentless disruptions. They accomplished this faster than the automobile industry came to dominate the roads, as evident in the celebration of “sidewalk superintendents”compared to the contentious reproach of “jaywalkers.”

The importance of mobility in Canada’s history can hardly be overstated. The built waterways, railways, and roadways that allowed for the movement of peoples, goods, and ideas within the country have long been considered cultural icons conveying collective ideas of Canadian identity. Yet, little has been written on the history of the modern construction machines that made this mobility infrastructure possible after Confederation, along with their designers, manufacturers, and operators. This article helps fill that gap by examining the technological development, manufacturing, and commercialization of earthmoving equipment in Canada (especially Ontario) in the 1860s–1920s, a period of great construction activity, including two of the world’s largest civil engineering and earthmoving projects and one of the fastest-expanding road networks in North America. It discusses the role of the federal, provincial, and municipal governments in developing, adopting, and disseminating this technology, and their ultimate reliance on American manufacturers despite the National Policy’s protectionism. This article supports the argument that technological development in Canada during the Second Industrial Revolution was continentally integrated in ways that involved technological dialogue with American companies, associations, and publications. While this manufacturing sector became dominated by American corporations by the First World War, the extent to and manner by which that happened varied depending on the type of machinery and the construction sectors in which they were used. The technological transition from steam-powered machines to electric, gasoline, and diesel motors and how it impacted Canadian manufacturers are also discussed.

This article examines the pro-colonialist propaganda and lobbying campaign by the American public relations firm Selvage & Lee on behalf of the Overseas Companies of Portugal and its ties with the Estado Novo during the Presidency of John F. Kennedy, the height of decolonization in Africa, and the start of the Portuguese Colonial Wars in Angola, Portuguese Guinea, and Mozambique. It takes a close look at the non-diplomatic activities of these “foreign agents” and their clandestine collusion with Portuguese government officials revealed by a Senate Committee on Foreign Relations investigation, which led to the 1966 amendments to the Foreign Agents Registration Act. Besides contributing to the growing historiography on international public relations, this article also introduces an Anglophone dimension to the study of lusotropicalism outside of the “Lusophone world” by exploring some of the channels through which its pro-miscegenation ideas were disseminated among American conservatives, including right-wing African-American intellectuals. The article can be downloaded here.

This article examines the transnational and international politics and motivations behind the Eurocentric campaigns of Portuguese American heritage advocates to memorialize the sixteenth-century navigators Miguel Corte-Real and Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo as the ‘‘discoverers’’ of the United States’ Atlantic and Pacific coasts, and how those campaigns were framed by the advocates’ ‘‘ancestral’’ homeland’s imperialist propaganda. It argues that the study of public memory and heritage politics can offer valuable insights into the processes of diaspora building and helps reveal the asymmetrical power relations often missing in discussions about cultural hybridity. The article can be downloaded here.

The sovereignty of migration policy makers is never absolute. This has been true for both receiving and sending states. One important check on the receiving nation’s immigration policy implementation was the sending nation’s own sovereignty over its expatriated citizens. These colliding sovereignties sometimes created liminal spaces where migrants and their facilitators were able to subvert regulations by playing them against each other, while other times they were ground between gatekeepers bent on enforcing their policies. This bilateral dimension is often missing from Canadian immigration history, as is the role of homeland government officials, who brokered and supervised these migrant movements while conciliating the roles of gatekeepers and facilitators. This is especially significant when it involved authoritarian governments, like Portugal’s Estado Novo dictatorship (1933-74). How did Ottawa’s relatively liberal immigration policies correspond with the Estado Novo‘s authoritarian stance on emigration? How did Portuguese officials influence the movement of its emigrants in Canada? How did the migrants react to the concerted top-down arrangements of two imposing governments? This article examines these and other questions in reference to the Portuguese “bulk order” and family sponsorship movements to Canada, between 1953 and 1974. The article can be downloaded here.

R. Costa, E. da Silva, G. Fernandes, S. Miranda and A. St. Onge, “Archiving from Below: Preserving, Problematizing and Democratizing the Collective Memory of Portuguese Canadians – The Portuguese Canadian History Project,” in Identity Palimpsests: Ethnic Archiving in the United States and Canada, ed. Amalia S. Levi and Dominique Daniel. Sacramento: Litwin Press, 2014

Until recently, the few archival records “representing” Portuguese immigrants in Canadian archives were those produced by governments and reflected a “top-down”, uniform perception of the Portuguese-Canadian experience. This chapter explores the “bottom up” motivations, principles, and work of the Portuguese Canadian History Project in its efforts to facilitate the donation of community records to a public archive and bridging the gap between immigrant and academic communities.

This article examines the changing political attitudes of Portuguese immigrants in Canada from the arrival of the first cohort in the 1950s to the emergence of the second and third generations in Canadian mainstream society in the 1990s. It explores historical factors that have influenced the political profile of Portuguese Canadians, including its predominantly working-class makeup; its lack of formal education and democratic culture resulting from Portugal’s authoritarian legacy; and its internal factionalism along regional, ideological, generational, and class lines. Fernandes offers a historical critique of sociological models— “socio-economic status” and “socialization”—commonly used for measuring and explaining immigrant political participation, and stresses the importance of diachronic studies in dispelling essentialist assumptions regarding immigrant communities. The author argues that generalist notions of “political participation” and “political constituency” miss important distinctions between representative and direct forms of political action, collective mobilization and individual activism, as well as state level and grassroots politics. He claims that each of these political processes operates according to its own distinct internal dynamics, at times responsive, at other times alienated from one another, which must be analyzed using appropriate scales of observation (macro and micro). The article can be downloaded here.

SELECT BLOG POSTS

“Time is of the essence out in the fields. When to seed, water, feed, harvest or cure are decisions that dictate the fortune of crops and cause farmers to lose sleep. Laying in their own beds, own homes, own land, own country, where they raise their families and where many were raised themselves, most farmers would say that their stressful love of farming is permanent. Food is temporary. If left alone, its natural fate is to rot. It truly only becomes food when eaten. Such a simple and usually inattentive act, yet so fundamentally constitutive to all societies. Not just in an obvious biological sense, but also culturally, economically, emotionally, and in whatever other ways people make sense of their individual and collective identities through food; including those who preoccupy themselves with that annoyingly persistent question, what it means to be Canadian.

If we are what we eat, what then are those who feed us? For nearly six decades, immigration officials have asked that same question and decided that the over 70,000 temporary migrant workers from the Global South, whose seasonal labour has been critical to every stage of the annual farming cycle, are not to be Canadian. They don’t get to stay.”

“On Guard for Canadian Parochialism,” Parts one, two, and three, ActiveHistory.ca, September 8, 15, 22, 2015

Since coming into power in 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper has taken various steps to redefine Canadian citizenship and reassert its “value” under a territorial, militaristic, loyalist, conformist and Anglocentric interpretation. As numerous commentators have noted, these reforms have unfolded within Harper’s broader campaign to (re)define the meaning of being Canadian along conservative ideals and British traditions. Conservative officials deny the existence of such underlying “agenda,” arguing their reforms simply addressed specific problems in the system, such as massive fraud and application backlogs. Recent citizenship debates in English Canada have dwelt mostly on the question of whether it is a right or a privilege; on issues of legality and process; and on measures of loyalty, attachment or worthiness. But there is more to it. In this three-part series, I will explore the historical narratives and political myths supporting the Conservative government’s parochial views on Canadian citizenship, and how they affect Canada’s and its expats’ place in the world. Part one will focus on the policies; part two on the historians; and part three on Canada’s diasporas.

“It is often said that Toronto is a city of neighbourhoods, each with its own socioeconomic characteristics, ethnic communities, life cycles and histories. While that may be true, Toronto is also a cluster of “invisible cities”, to use the words of Italo Calvino. Their diverse citizens have developed their own mental maps of the city, which are often juxtaposed yet distant from each other or unable to communicate. In these alternative geographies, Toronto is not just the largest city in Canada, or simply the capital of Ontario, but also a transnational ‘suburb’ of the places where its vast immigrant population comes from.

(…) Toronto is host, and home, to a great many immigrant communities, whose family, cultural, economic, and political realities traverse local and global contexts. Toronto’s streets and squares merge with those of their home towns and cities – alternative geographies ‘invisible’ to those who ignore them. We all live in someone else’s land. To know the citizens of these juxtaposed cities and their transnational realities is to grow our common ground, which is where democracy ultimately happens and Toronto increasingly lives.”

Leave a comment